Rowan LeCompte first came to Washington National Cathedral in the summer of 1939, as a 14 year-old on a tour. He was born on St. Patrick’s Day in 1925, in Baltimore, Maryland, and, while raised in a family circle that included interests in music, painting and architecture, he arrived at Washington National Cathedral with no specific interest in stained glass. The day trip to Washington, and thus to the cathedral, was provided by a visiting aunt. Until that time, Rowan’s knowledge of Washington’s cathedral was informed, primarily, by an article in an old National Geographic Magazine, but, even at a distance, he knew it when he saw it. The cab turned up Massachusetts Avenue.

The windows in Washington National Cathedral’s Glover Bay, by Rowan LeCompte, celebrate the founding of the Washington National Cathedral in the home of Charles Glover.

I’ll let Rowan, himself, tell you of what came next…

“In those days one entered on the South Transept steps which were made of concrete, and you walked up to a great piece of un-built structure which was covered with tar paper and came to a big tin door in a tin wall which was covered with scaffolding. The door opened, and we came into a space that from the outside seemed to be black, but once in the door I could see we were in a magic twilight, a heavenly place. I had never seen such a thing! A great, soaring, mysterious space and it was filled, to my delight, with music. The organ, which had just been installed, was being used for practice. And the great Handel Largo from “Ombra mai fu”, was one. It was known in those days as Handel’s Largo. But in any case, the organist was playing an organ transcription of it. And the awe of the interior, the dim light, the magic of the North Rose shining there in the gloom,…it wasn’t gloom; it was mystery. It was anything but gloom. It was a magic place. And filled with a degree of awesomeness and beauty and spirit. How else can I say it, that I had never seen in my life before, or experienced. And I was simply struck, if not dumb, I was certainly bowled over.”

Rowan returned to the Cathedral a few times that year, and on a visit in October he took note of Lawrence Saint’s “Moses” window. That moment would remain Rowan’s oldest specific memory of an attraction to the art of stained glass, throughout his life. Following that moment, he returned to Baltimore, got books on stained glass from the Enoch Pratt Free Library, and taught himself how to design and fabricate small glass panels on the living room floor of the family home. There’s an architectural tradition in Baltimore of stained glass panels in the transoms above the row house front doors, which resulted in the presence of small stained glass shops in almost every neighborhood. Rowan’s first creations were made from glass scraps collected from nearby stained glass shops.

By this time, Rowan had developed what I like to refer to as “The Cathedral Bug”. Anyone who knows me well knows what I’m talking about. The Cathedral Bug is a heart and mind possessing attraction to cathedrals, particularly Gothic cathedrals. I’d imagine the Cathedral Bug is a much older affliction than our cases at Washington National Cathedral, but all of my experiences of it have been at Washington. Anyway, Rowan had it, and he had it bad. Living in Baltimore, his solution became the Episcopal Pro-Cathedral of the Incarnation, a Gothic-style church, being built as the Synod Hall for a larger (eventually not built) cathedral, under the direction of Philip Hubert Frohman, also the senior architect at Washington National Cathedral.

Designed by Philip Frohman, Baltimore’s Cathedral of the Incarnation was originally intended as the Synod Hall for a larger cathedral. The larger cathedral was never built.

Rowan’s repeated presence at the pro-cathedral was noticed by that church’s senior canon, Harold Arrowsmith, who eventually also became aware of Rowan’s interested in stained glass. Then, on yet another day that would bear heavily on the rest of Rowan’s life, Canon Arrowsmith introduced Rowan LeCompte to Philip Hubert Frohman. It was a day that would change the course of art and architectural history.

Washington National Cathedral architect, Philip Hubert Frohman, depicted in the Ascension mosaic in Resurrection Chapel.

Rowan developed a relationship with Mr. Frohman, who freely shared his opinions on stained glass; that stained glass should inspire, exhibiting “richness and sparkle”. Mr. Frohman taught the young stained glass artist how to properly present his work and offered commentary on some of the small projects Rowan had already completed. Eventually, Mr. Frohman invited the young artist to produce drawings for a small window space, in a small crypt level chapel, at Washington National Cathedral. When completed, Mr. Frohman would take the plans to the Cathedral’s Building Committee, but, just before he did, he turned to the young LeCompte and asked, “By the way, Mr. LeCompte, how old are you?” When Rowan replied that he was 16 years old, Mr. Frohman responded, “Good God… I’d thought you were older.” When Mr. Frohman returned from the Building Committee, with approval for Rowan to produce a window for Washington National Cathedral, well, I’ll let Rowan explain it…

“Everything went blurry before me, and really I had never experienced such extremes of joy as I did then. Never.”

Rowan LeCompte installed his first window at Washington National Cathedral at the age of 16.

Rowan LeCompte depicted in the Ascension mosaic in Washington National Cathedral’s Resurrection Chapel

At the age of 18, in 1943, Rowan went into the U.S. Army, and his active service would take him from foxhole-to-foxhole, from Normandy, France to Germany. Along the way, he formed a lifelong friendship with one of his unit buddies, Charlie Matz. As Charlie and Rowan fought their way across France, leave from their duties would occasionally allow them to visit some of the great, French Gothic cathedrals. Along the way, Rowan, somehow, managed to infect Charlie with the “Cathedral Bug”. When Charlie returned from the war, he attended a seminary and eventually ended up assisting Rowan with the iconography of some of his greatest works. At the same time, from foxhole-to-foxhole across northwestern Europe, Charlie managed to infect Rowan with an interest in Charlie’s sister, Irene. On returning from the war, Rowan would marry Charlie’s sister, and return to the pursuit of his art with Irene Matz as a working partner.

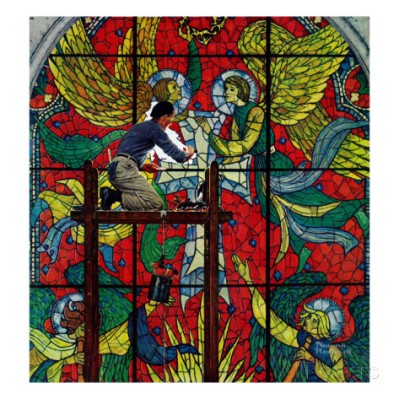

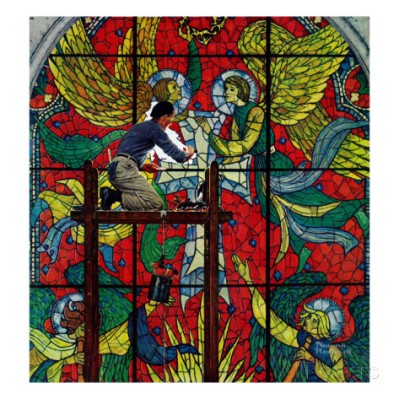

Stained Glass Window by Norman Rockwell

By 1960, Irene and Rowan had earned some attention for their work and notoriety as experts in the field of stained glass. Around that same time, painter Norman Rockwell decided to attempt to reproduce a scene he had witnessed years before at Westminster Abbey; a workman, perched on scaffolding, repairing stained glass. Reproducing the look of stained glass, however, gave Rockwell trouble, and he turned to Rowan and Irene for advice. In the end, in Rockwell’s painting “Stained Glass Window”, the window’s design is based on a plan submitted by LeCompte for a window at National City Christian Church in Washington, D.C., and the workman depicted in the painting is the same workman that Rockwell witnessed that day at the Abbey; Rowan LeCompte.

At some point in the late-1950s or early-1960s, someone at Washington National Cathedral decided the six blank stone panels on the walls of Resurrection Chapel, were simply too blank. Mr. Frohman had first envisioned the small Norman-style chapel as being completely encrusted in mosaic and glass, in the tradition of the eastern Orthodox churches. In Frohman’s thinking, this was an obscure reference to the Norman churches of Sicily, the only location where Norman architecture had crossed with eastern Orthodox embellishment. However, decades earlier, the Cathedral’s Building Committee had decided such a plan was simply too much, and opted instead for one beautiful Hildreth Meier mosaic over the chapel’s altar. So, in reconsidering mosaics for the Resurrection side panels, the Cathedral approached Rowan and Irene for any artist recommendations they might be able to make. The LeComptes knew no mosaic designers, nor had they ever done mosaic work themselves. Then, after explaining that the mosaic fabrication would be done by one of the world’s leading mosaic fabricators, the Cathedral offered the design commission to Rowan and Irene. Thus did Rowan LeCompte, amidst his rise to prominence as a stained glass designer, add mosaics to his portfolio. During the design, fabrication and installation of these mosaics, the six appearances of Jesus after the Resurrection, Irene became ill. She passed away in 1970, during the installation of the fourth mosaic panel, “Doubting Thomas”. The sixth panel, the “Ascension” panel, was designed to include self-portraits of Rowan and Irene. In a turn unusual for an artist, Rowan paid to be the donor of the final panel and to have it dedicated to Irene’s memory.

Irene Matz LeCompte depicted in the Ascension mosaic, in Washington National Cathedral’s Resurrection Chapel. The Ascension mosaic is dedicated to Irene’s memory.

In the 1970s, Rowan would receive the largest and most important commissions of his life; those for Washington National Cathedral’s west rose window, “Creation”, and for all 18 of the Cathedral’s three-story high, nave clerestory windows.

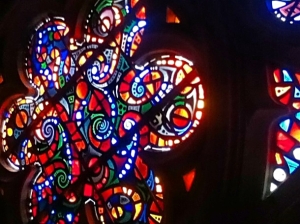

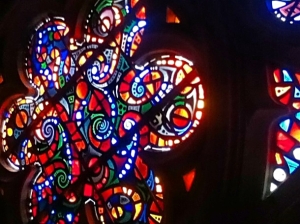

A close look at Rowan LeCompte’s masterpiece, Creation, the west rose window at Washington National Cathedral.

“Creation”, considered by some to be among the most beautiful windows in all of Christendom, was dedicated on Easter Sunday in 1976. The commission for the 18 clerestory would be completed over the following 25 years. Rowan LeCompte delivered his final window, a reworking of an earlier window, to Washington National Cathedral at the age of 86, and the last time he walked out, at the end of a career spanning seven decades, he walked out one of the leading lights of stained glass design in human history.

The last time I spent with Rowan was several years ago, when he brought a small group of people from his retirement community to the Cathedral and gave them a brief tour of the glass in the north nave outer aisle. During that tour, while presenting a set of windows by Irvin Bossanyi, Rowan turned to his guests and said, “Now, this man was a REAL artist.” I knew immediately Rowan was referring to the fact that Bossanyi had worked in many different media, but Rowan’s guests tittered at the apparent display of modesty that let this one great artist refer to another great artist as a “REAL” artist. At the end of the tour, I took the opportunity to confirm my understanding of that moment, and Rowan agreed. Perhaps “multi-media artist” might have been a more appropriate term for what he had meant to say. I explained that, as a Cathedral Docent, one of the things I love to do most is tell his story. How then should I describe him, if not as a “REAL” artist? “You just tell them,” he confided, “I was just the luckiest 14 year-old to ever walk into the room.”

Sunlight pouring through Rowan LeCompte’s windows in Washington National Cathedral’s south nave clerestory, bathe the surrounding architecture in cascades of color.

Rowan LeCompte passed away on February 11, 2014, at his home in Waynesboro, Virginia. A service celebrating his life and his work will be held at Washington National Cathedral, with his family, his friends and surrounded by his life’s work, on Monday, July 21, 2014. With the way art tends to last in buildings like Washington National Cathedral, Rowan LeCompte’s star should continue to rise for centuries to come, and I fervently believe he will eventually be regarded as one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. Tomorrow, we send him on his way.